In The News

North Carolina Coalition for Charter Schools

Meet the innovator who launched the Charlotte area’s first trade high school

By Kristen Blair November 17, 2025 News

“This wasn’t going to be a vocational program where students would build birdhouses, bake cookies, and sew aprons. This was going to be a robust four-year program that would give students the ability to walk right in the door and start working.”

-Jennifer Nichols

Students from Aspire Trade High School (ATHS). All photos courtesy of ATHS.

In 2023, following years of planning, Jennifer Nichols helped launch Aspire Trade High School in Huntersville. A public charter school, Aspire is also the first trade high school in the Charlotte area. The school was founded by the Aspire Carolinas Foundation, which also established The Halton School on the same property to serve students with Asperger’s and autism.

At Aspire Trade High School (ATHS), students pursue general education coursework along with training in 11 trades. Aspire currently serves 300 students in grades 9-12, and its first cohort of seniors will graduate this spring.

A former teacher and nonprofit leader, Nichols now serves as Aspire’s executive director and principal. Kristen Blair, the Coalition’s communications director, spoke with Nichols to learn more about the school, the importance of career and technical education (CTE), challenges in opening a charter school, and more. We include the Q&A below.

You began your career as a teacher in Michigan, later working in the nonprofit sector before returning to K-12 education. What led you to a charter school—and to Aspire Trade High School?

Jennifer Nichols, the executive director and principal at ATHS.

Jennifer Nichols: When I left Michigan, I shifted career paths for a period of time and worked in sales and the nonprofit sector. I later returned to education to work at a private, independent school, The John Crosland School, in Charlotte. While there, I began to see the difficulties for students who didn’t fit the traditional four-year “go to college out of high school” traditional pathway. Parents from The John Crosland School represented eight different counties and they were desperately trying to find a place for their child but many would walk away crying because they couldn’t get their kids to the school; it was too far away.

I did, however, see some schools serving kids who “didn’t fit the mold,” but they were on a smaller scale, and they were in pockets closer to Charlotte.

So, I talked to the late philanthropist Dale Halton about it. “I’m constantly seeing parents walk away crying,” I said. “I can’t keep turning students away without doing something to meet the actual needs.”

We started the Aspire Carolinas Foundation in 2017. Our original goal was to start a private school and work with students with Asperger’s, students on the autism spectrum and students with learning differences. As we searched in the North Mecklenburg area, the late Jill Swain, former mayor of Huntersville, asked to speak with me. “We have a group of people who have been trying to get a trade high school up here [the Huntersville area],” she said. “CMS [Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools] has been talking to us for two years, but nothing is happening. People are getting really frustrated.”

We began discussions with Ms. Swain, business leaders, and board members of the foundation. We could see the need, but we knew it would take a lot more than we had at the time—and we weren’t sure if it fit our mission or if we could take on a project of that magnitude. But our board realized that the students we planned to serve were already outside of the general education path. We thought, “If not us, then who? Why not add another group of diverse learners?”

We found this incredible piece of land on 23.5 acres. It already had a historic building on the property that could be renovated for the private school. We began thinking about what we wanted for the trade school. This wasn’t going to be a vocational program where students would build birdhouses, bake cookies, and sew aprons. This was going to be a robust four-year program that would give students the ability to walk right in the door and start working. That’s how we got here.

As Aspire’s website notes, the school is the first trade high school in the Charlotte area. Why is it so important to offer a path for students seeking career and technical education (CTE) options?

Nichols: I know they had vocational schools a long time ago in North Carolina, but they just stopped having them. Where I’m from in Michigan, our vocational school eventually became a CTE school. It just grew to become a more technologically savvy school. But it’s still there and it actually expanded.

There are schools in other parts of the country, but there are not nearly as many as we need because our workforce is aging and retiring. This isn’t just a North Carolina problem, although it is a big North Carolina problem. There are states that held on to their vocational programs, and they have become larger CTE programs that are broader in their mission. But they also don’t tend to be brick and mortar buildings where it’s a high school with this concept.

Why can’t these schools be a one stop shop for a high school? Why can’t it be a trade school with a traditional high school experience? We don’t have sports, but we’re doing our own Phoenix Wars between our trade groups. We’ll still have a homecoming court and dance as well as prom and graduation. We’re finding non-traditional ways of doing traditional things.

We have students who are going to finish their education while they’re on the job. They’ll come out with around 2,000 hours toward licensure, but they’ll finish those up with the large companies they are going to work for.

Could you share more about Aspire’s educational approach and the emphasis on hands-on career training and a project-based academic program? What does that look like day to day?

Nichols: Every day our students are taking core classes: science, math, social studies, language arts. They must pass those classes to get their general education requirements done. But every day they also go to their trade pathway class. They are working in the automotive lab, culinary lab, welding shop, HVAC, plumbing, electrical. [See the list of 11 trade programs taught at Aspire.]

In their senior year, they do an apprenticeship and choose where they want to work. We have multiple companies that will come in to interview. A lot of students will go with their apprenticeship companies, but that doesn’t mean they have to.

How does the charter model provide you with the flexibility to fulfill your mission?

Nichols: It’s hard to do this in a traditional public school because I need experts in automotive, HVAC, plumbing, welding, culinary, IT, medical assisting, etc. Most likely that means they don’t have an education background. So, we have to find someone who has the passion to teach the next generation what they have loved and worked in as their career path. We had to find a plumber who could also be a plumbing instructor. We had to find an HVAC technician who would also love to teach students HVAC. That’s not as easy as one would suppose. We’re turning technicians and passionate career-minded individuals into classroom instructors.

All of our instructors are in a licensure program: They’re all being asked to become licensed CTE instructors. We’re asking some people who are 25 years into their career path to go back to school and get licensed. It’s a heavier lift than people realize, but it’s very doable. These are people who are passionate and want to see this generation grow and learn that specific trade. This is what leaving a legacy is all about.

As an operator at a relatively new charter school, how would you characterize the challenges of launching a charter school in North Carolina right now?

Nichols: We have the typical charter challenges as well as other challenges. One of the typical challenges is finding good people. When you open any business, you don’t have a foundational base of individuals. So, you fish in one pond—it’s the people who are looking for a job today. Your first year, all of your people are new. Finding the right people to become trade instructors and educators as well as qualified core content instructors is very hard to do, especially during a teacher shortage.

As a charter school, you also have a limited budget since you’re not getting the same funds as a traditional public school. As an independent nonprofit [without the backing of a charter management organization or education management organization], you don’t have the big company behind you that’s going to hold money in reserve to make sure you are going to be successful. So, it’s all on you.

We’re where most charter schools are in the third year. We’re finding our base and we’re stabilizing. Then you have to start thinking about renewal: Are we doing everything we need to do?

How have your experiences as a charter leader impacted your views about what works in education?

Nichols: Thirty percent of students in the traditional student population are not college preparatory students and need a different career pathway. Oftentimes, their needs are not being met in the traditional school setting. I have labs in our building that are full of equipment you wouldn’t find in a traditional school. These schools are needed to develop the next generation of skilled workers.

At Aspire Trade High School, we are a completely project-based school, even in our content subjects. Our students learn by doing. Is there a way to do that in traditional public high schools? There could be, but right now, I don’t see it happening.

What do you see as the opportunities and challenges ahead for North Carolina’s charter sector?

Nichols: The charter school industry faces funding challenges. Until we start finding equity in education, charter schools are going to have issues of staying solvent. Every charter school is under-funded as long as it is not getting the same funding as the traditional public school. How do you meet the financial needs when there is no equity between the charter school and the traditional public school? That’s one challenge. The other challenge is the battle of meeting your students’ needs on a smaller budget—because you are a public school and you must fulfill all of the requirements of being a public school.

Then you look at the challenges of schools like ours. We’ve gone into those low-income communities. We’re giving an equal opportunity to every student to be successful. That’s the other problem with the general education model: Are we really helping our low-income students? Do they really have equal opportunity?

There are also a lot of challenges in being a non-traditional school. We are not an alternative school. We are a very robust, skill-based school; our students are learning to be technicians in their fields. Our students know how to repair a car. They change the oil on the buses. Our students are learning incredible skills, and they’re just growing and changing every day. But the state wants us to fit into the traditional mold. They don’t know how to grade us. We don’t have the full bell curve, but they want to grade us on the bell curve that they expect in every other school. We have only a handful of students who will go on to college and we don’t have students who necessarily test well. However, we do have students who will be very successful in school and life when given the opportunities that exist at ATHS.

Is there anything I didn’t ask that you believe is a key part of this conversation?

Nichols: I want more people to jump in the water. We want to be change agents. A group from Stokes County that wants to do a charter trade high school is coming to take a look at our school model because they understand the need. But it’s not an easy lift because we’re still being measured by the old measuring stick. More people need to be open to this concept. Who doesn’t need a good plumber or automotive technician? We desperately need this type of school model, especially if we are going to be prepared to answer to the deficit of trade workers in the next 10-25 years.

We not only need [these students], but it’s really our responsibility to prepare them. Thirty percent of our students today need a school like this, and we need more of them. Our educational platform needs to expand and grow to meet the needs of that 30 percent, because that 30 percent is going to meet our needs. We’re growing our own skilled workforce. We really can build a pipeline, but our educational system needs to expand. How do we achieve this growth? At ATHS, we say, “Grow your own!”

Read more about Aspire Trade High School from Charlotte Magazine or Lake Norman Publications. Visit the school’s website.

Metal Center News – The Workforce of the Future – Finding The Next Gen From the Ground Up

By Karen Zajac-Frazee on Nov 13, 2024

A variety of schools and organizations are introducing people of all ages to the possibilities available in manufacturing.

Jennifer Nichols, Executive Director, Principal, Aspire Trade High School, Huntersville, N. C.

Students in this trade high school come in as freshmen and choose a path. They don’t typically change as it’s a rigorous program. The school currently offers welding and fabrication, carpentry, masonry, HVAC, plumbing, auto collision, medical assisting and medical coding, as well as a culinary program. In the future, the school is planning on adding a hydroponic program, along with horticulture.

These students go to their trade every single day for four years, all year, except for their senior year where in the second semester they will spend time in apprenticeships. “When they’re not in their lab, there is a companion class that goes along with it so that they can get the soft skills. That companion class is the promise we made to our partners,” states Nichols.

Furthermore, Nichols says the students are using industry-standard tools and equipment and the National Center for Construction Education and Research curriculum. “Then, in May of their senior year, they’ll actually put in applications for the companies and most of them should have their position before they walk the stage.”

They come out, concludes Nichols, with what one would get in a two-year community college program in the trades. Nichols describes this as Level 3 Ready-To-Go-To-Work.

On Your Side Tonight WBTV Interview with Jamie Boll and Jennifer Nichols

CHARLOTTE MAGAZINE

‘It’s a Good Time to Be a Plumber’: A Look Inside Charlotte’s New Public Trade High School

Aspire High, North Carolina’s first public trade high school, trains the next generation of workers. For local companies, the students can’t graduate soon enough

September 3, 2024/Jen Tota McGivney

Photos by Herman Nicholson

“Are We Doomed?” In this University of Chicago course, students learn how humans might meet our collective demise. Nuclear weapons, climate change, artificial intelligence: Experts across fields come as guest speakers who share predictions of the threats that might end us all.

A recent New Yorker story shared how Geoffrey Hinton, a former AI developer and now a harbinger of its risks, attempted to temper the doom in this class earlier this year. Asked how to navigate a changing world, the 76-year-old offered students two pieces of advice. His first tip, a joke: It’s a good time to be an old person. His second tip, more serious: It’s a good time to be a plumber.

AI can do a lot of things, but it can’t work with its hands. ChatGPT can read the entire Internet, but it can’t fix a toilet. It can’t build a deck. Soon, it may be a safer career option to become a plumber or a carpenter than, perhaps (whimper), a writer.

The U.S. faces a shortage of skilled trade workers. Ask anyone who’s needed a tradesperson lately, and they’ll tell you. Ask me! I’ll tell you about the delays on a home project last year due to a lack of local electricians and carpenters. Ask Justin Elliott! He’s the president of Precision Plumbing in Matthews, and he’s dealt with workforce shortages for decades.

“It’s a problem. I’ve been at Precision for 25 years, and (labor shortages) have been a problem as long as I’ve been here,” Elliott says. “In the next five years, probably 25% to 50% of my top talent will be retiring. They’ve got a skill set that is just not learned from a book; it’s learned through experience and hands-on learning. As they retire, that knowledge retires with them.”

This sounds like opportunity to the students at Aspire Trade High School in Huntersville. While the students in Chicago ponder how things may go poorly, future plumbers, electricians, and welders are here to study under experts and prepare to enter the workforce with an increasingly rare and in-demand skill: making a living by working with their hands.

Aspire, which opened in 2023, is the first public trade high school in North Carolina. Students can choose from 10 trades—including masonry, HVAC, plumbing, medical coding, and culinary—as they take mandatory core classes in English, math, and social studies. By the time these teenagers graduate, they’ll have high school diplomas as well as certificates in their trades. Graduates can choose to pursue four-year degrees or use their credentials to work in a job market that demands their skills right now.

This is an especially attractive option for students unsure about whether they want, need, or can pursue four-year degrees, or those who don’t learn well in traditional classroom environments. As trade programs for high schoolers have declined over the past few decades in favor of curricula geared toward standardized testing, these students’ strengths have often been neglected.

“Parents who have hands-on kids worry that the typical school environment is not going to prepare that student for a career opportunity,” says Jennifer Nichols, Aspire’s principal. “When parents hear about us, they’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is so amazing,’ because it’s an opportunity they never thought they’d have. … (Students) are getting a $30,000 education for free in this building, and they’re coming out with basically what they would have picked up with an associate’s (degree) from a community college.”

As a public school, Aspire is free to attend, and it draws students from around the Charlotte area. All students learn from experienced trade professionals, many of whom have owned their own businesses. The school prioritizes socioeconomic diversity, weighting its enrollment lottery to ensure at least 30% of students come from low-income homes. On one level, this school may change the trajectory of the lives of its students. On another, it displays how our city might start to reverse its notorious lack of upward social mobility by creating more opportunities for more people.

Ebony Covington’s son, Nigel, has always been a good student and curious learner. At his middle school, he took all honors classes in an International Baccalaureate program, which focuses on critical thinking and global awareness. But Nigel, 15, is a hands-on learner who wanted to take what he learned in books and use it to create things, to observe how those concepts work in the real world. It’s a style of learning seldom offered in typical classrooms.

“He wants to be as prepared as possible,” Covington says. “He doesn’t want to be put into a box. He goes back and forth about what he wants to do, as most kids do, because he has many interests.”

One day in eighth grade, Nigel brought home a brochure about a trade high school that would soon open in Huntersville. He pitched the idea to his mom: At Aspire, he could keep his options open. If he wanted to go on to a four-year college right after high school, he could; if he wanted to work for a few years first or pursue a career without a four-year degree, he could do that, too. But mostly, he could learn in an environment that would let him use his hands and take breaks from a desk. His enthusiasm sold his mother. Since Covington enrolled him as a freshman last year, she’s watched him become a more confident, enthusiastic student.

“Back when he was in elementary and middle school in a more traditional setting, I’d ask him what he learned that day at school, and he’d just say, ‘Nothing, really,’” Covington says. “Whereas now at Aspire, he has something to talk about each day. Even if he’s talking about English class, he’s still excited about what he learned that day.”

Nigel, attracted to the idea of creating things from metal, chose to study welding. Even as freshmen, he and his classmates learned welding basics while doing real work: They helped install metal lockers and worked in a lab with the same tools that professionals use.SteelFab, a Charlotte-based company and one of the largest steel fabricators in the country, sponsors Aspire’s welding lab. Precision Plumbing advised the school in setting up the plumbing lab down the hall. Upstairs, Atrium Health sponsors the medical assisting and coding lab. Each program has a relationship with a local company, which helps set up labs and advises on curricula. Before students begin paid apprenticeships during their senior years, they’re already familiar with the equipment, terminology, and practices of local employers.

When Nigel graduates in 2027, he’ll have a high school diploma, but he’ll also have a level-three certificate and an apprenticeship with SteelFab that will qualify him for a job if he chooses to enter welding.

But what Nigel won’t need to get that first good job? College debt.

For the past few decades, the goal of high school has been to prepare students for a four-year degree, which, the assumption goes, is required to make a good living in the 21st century. That assumption is changing.

The college debt crisis has prompted a rethinking of educational expectations. Over the last 20 years, in-state tuition at public universities has increased about 56%, adjusted for inflation (158% not adjusted). The average person with a bachelor’s degree graduates with nearly $30,000 of debt. Effects of so much debt, so young, can be crippling long after graduation. It can delay or quash plans to buy a home, start a family, and even retire.

Is a four-year degree necessary? It depends on the student and their plans. Robert Farrington is a personal finance expert and the founder of The College Investor, which coaches millennials to get out of debt and start investing. He hopes more students and parents challenge the notion that a four-year degree is for everyone.

“I’m very bullish on trade school in general,” Farrington says. “When you look at the pendulum of where high school graduates are going, for the last 15 years or so, it’s been—very much been—all four-year traditional college. But then in the last two or three years, people have really started to think twice about that and realize that there’s a lot of other options out there.”

Aspire’s mission is to show students how many options they have. When I talk with freshmen and sophomores—which, in Aspire’s first year, were its only students—the word “options” comes up in nearly every conversation. They consider multiple versions of their future selves: as journeymen, business owners, college graduates. This is intentional, Principal Nichols says. Aspire’s teachers have decades of experience and mentor students about the many ways they can use the skills they’re learning.

“It’s about the brainstorming. It’s about the whats, the whys, the ifs, and the what-could-bes,” Nichols says. “Our instructor-mentors will say, for example, ‘Did you know that you can weld underwater?’ And the students are like, ‘Whaaaat? You mean I can scuba dive and weld? What would I need to do to do that?’”

“The biggest thing is telling students that these jobs exist,” Farrington says. “There are so many jobs that are obscure because they’re not talked about, but they have the potential to be very lucrative.”

To make his point, Farrington tells me about the most in-demand trade job today: an elevator service technician. Think of the skill set. An elevator service technician must have mechanical skills as well as climbing skills. How many tall buildings does each city have, and how many people in each city have the experience to do this work? The average salary for this job in North Carolina is more than $110,000 a year. “If you went to a rock-climbing gym and told the teenagers there about this,” Farrington says, “some would probably be like, ‘Hey, that’s kind of cool.’”

Atrium Health, which sponsors the medical coding and assisting labs, also coaches Aspire students in their options. A health care company is a corporation, so it needs accountants, marketers, information technology specialists, and more. Graduates of Aspire’s medical coding or assisting programs can qualify for jobs at Atrium Health right out of high school, and after they’re established at the company, they can get tuition reimbursements to advance their careers at the company in clinical or non-clinical roles. It’s not only a foot in the door but a leg up.

“When a lot of students think of jobs in health care, they think of a doctor, they think of a nurse,” says KeWanda Thompson, a strategist with Atrium Health Community Engagement and Corporate Responsibility. “We do so much at Atrium that we have so many opportunities that a lot of people don’t understand. There are a lot of opportunities in non-clinical fields here, too.”

Whatever fields students choose to enter, trade skills can be a lifelong asset. Anyone who owns a home or a car knows how expensive carpentry, plumbing, or mechanical work can be. It’s a point that Jack Whitley, an auto shop instructor at Aspire, taught his students with the help of a 1967 Chevrolet Chevelle. The car is beautiful, seemingly mint condition—half of it, anyway. The Chevelle’s other half reveals the car’s true history: It had been left for junk, forgotten under a tree in Huntersville for years. Whitley offered its owner $1,000 to prove a point to his students: What can they accomplish with this car and $1,000 in parts?

When freshmen and sophomores first entered Whitley’s class last year, “most didn’t know a lug wrench from a floor jack,” he joked. By the end of the year, he’d taught them how to sand, repair dents and holes, and paint. He kept half of the Chevelle in its original state so they could see how far they’d come by fixing up the other half.

“I tell them,” Whitley says, “you can take a $1,000 car and turn it into an $8,000 or $9,000 car with some hard work.”

One of the students who worked on the Chevelle was sophomore Braxton Raymond Becker. Braxton had never worked on a car before this one, and he beams with pride as he tells me about the work he and his classmates did to turn this Chevelle into a beauty. Braxton doesn’t know whether he’ll pursue a career in auto body repair, although he does like the idea of owning his own shop one day. But he’s discovered how much he enjoys working with cars—and how those skills can translate to good money.

“If I can have a good-paying job after high school for four or five years,” he says, “then I can help pay for college if I decide to do that.”

Aspire students cover a range of learners. Some, like Nigel, come from honors programs. Some have autism, ADHD, or other conditions that can make it difficult to learn in a traditional setting. Some are children of immigrants who have been in the country only a few years, while others are children of Charlotte natives. About 360 students attend this year, and the enrollment will reach 523 once all four classes—freshmen to seniors—have filled.

“We give more students the opportunity to be successful,” Principal Nichols says. “We’re a rigorous program, but we’re not one-size-fits-all.”

What the students share is a proclivity for hands-on, project-based learning—a trait that sometimes doesn’t show until their teen years. Elementary schools offer a lot of project-based learning, middle schools less so. By the time students hit high school, they wonder why they’ve begun to struggle. They didn’t change, but the teaching did. When such students move to Aspire, school starts to make sense again. And when they graduate with skills that companies need, their futures open. Aspire offers previously overlooked students a running start in lucrative, in-demand careers, some of which will literally help build this city.

“For a lot of these families, they’ve never been able to break cycles and create generational wealth. We’ve got a lot of families where this particular student is going to break out and do something that the family has always wanted their kids to do but didn’t dream they’d have the opportunity to do,” Nichols says. “If you take those students who really want to be successful and start mentoring them as freshmen, you’re going to see some really amazing professionals.”

Jamie Boll WBTV On Your Side Tonight Interview with Jennifer Nichols and Scott Whitlock.

We are delighted to share this news interview with you featuring Jamie Boll, our Executive Director – Jennifer Nichols, and our Tile and Masonry lab partner Scott Whitlock (Whitlock Builders). There are tremendous opportunities and careers available in trade and technical jobs and a high labor shortage for those positions right now. Our free charter trade high school will allow students to enter a trade position upon graduation with no need to take on additional college debt.

Aspire Trade High School video filmed in partnership with Nudura.

Nudura video featuring Aspire Carolinas Foundation – Executive Director – Jennifer Nichols.

Topping Out Ceremony – January 10, 2023

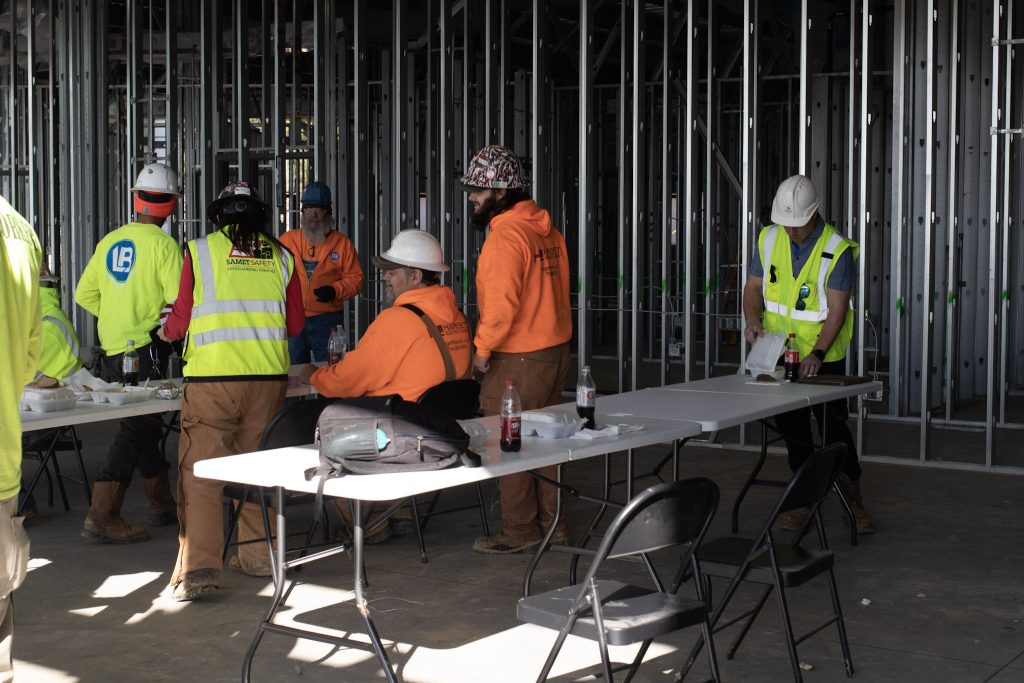

We are excited to share photos from the Aspire Trade High School Topping Out Ceremony! This is when the last steel beam is placed before the roof goes on the building. A big thank you to Samet, our construction team, and all our partners and supporters for their hard work and dedication!

Trade Exploration Day – October 8, 2022

A big thank you to everyone that came to our trade exploration day! We enjoyed meeting you and talking with you about our trade offerings at the high school.

Lake Norman Publications Article

We are excited to share this article by Lee Sullivan at the Lake Norman Media Group about our Aspire Trade School and Samet Building Corporation groundbreaking ceremony! Please click the link to view.

Aspire Trade High School and Samet Building Corporation – Groundbreaking Event.

June 9, 2022 – Aspire Carolinas Foundation was thrilled to host our groundbreaking event in partnership with Samet Building Corporation! The Aspire Trade High School is scheduled to open in the fall of 2023. This state-of-the-art building will be the first trade high school of its kind in Mecklenburg County. A big thank you to our Aspire Carolinas Foundation Board: Dale Halton, Jennifer Nichols, Jim Secunda, and Lauren Nicholson and all our partners: Boomerang Design, Burton Engineering, Concrete Supply, Nudura, Dryvit, Tremco, Trane Technologies, SteelFab, Müller Corporation, Precision Plumbing and Atrium for helping to make this project happen!